In this article, we will walk down memory lane back to the history we learned in school during our youth, of events and ideas that shaped the foundation of our nation. However, we shall uncover the truth behind the reasons such history truly took place, which is the underlying faith that carried them through trials and tribulations. We will discover how that faith played a crucial role in the founding of America, and the profound influence that would carry on for decades, permeating various aspects of life, governance, and culture. The advancement of the Kingdom of God was at the forefront of their minds daily and was the main purpose for the early colonies, guiding their decisions and aspirations as they sought to build a society grounded in spiritual principles. The colonies’ success was only possible due to God and the eternal joy that carried them through such difficult times, providing them solace and strength in moments of despair. They remained steadfast due to their unshakable faith in the word of God and high views of His Law, seeing each challenge as an opportunity to affirm their beliefs. There, they sought to do all things to the glory of the Lord and establish everything according to God’s higher law, ensuring that their endeavors reflected their dedication to divine ideals. This is the forgotten history that we were not fully taught, a narrative rich with lessons on perseverance, purpose, and the enduring power of faith that continues to resonate through generations.

While the people are virtuous they cannot be subdued; but when once they lose their virtue then will be ready to surrender their liberties to the first external or internal invader. No people will tamely surrender their Liberties, nor can any be easily subdued, when knowledge is diffused and virtue is preserved. – Samuel Adams

6. William Penn & Pennsylvania

The Prayer in the First Congress, A.D. 1774

O Lord our Heavenly Father, high and mighty King of kings, and Lord of lords, who dost from thy throne behold all the dwellers on earth and reignest with power supreme and uncontrolled over all the Kingdoms, Empires and Governments; look down in mercy, we beseech Thee, on these our American States, who have fled to Thee from the rod of the oppressor and thrown themselves on Thy gracious protection, desiring to be henceforth dependent only on Thee. To Thee have they appealed for the righteousness of their cause; to Thee do they now look up for that countenance and support, which Thou alone canst give. Take them, therefore, Heavenly Father, under Thy nurturing care; give them wisdom in Council and valor in the field; defeat the malicious designs of our cruel adversaries; convince them of the unrighteousness of their Cause and if they persist in their sanguinary purposes, of own unerring justice, sounding in their hearts, constrain them to drop the weapons of war from their unnerved hands in the day of battle!

Be Thou present, O God of wisdom, and direct the councils of this honorable assembly; enable them to settle things on the best and surest foundation. That the scene of blood may be speedily closed; that order, harmony and peace may be effectually restored, and truth and justice, religion and piety, prevail and flourish amongst the people. Preserve the health of their bodies and vigor of their minds; shower down on them and the millions they here represent, such temporal blessings as Thou seest expedient for them in this world and crown them with everlasting glory in the world to come. All this we ask in the name and through the merits of Jesus Christ, Thy Son and our Savior.

Amen.

Reverend Jacob Duché

Rector of Christ Church of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

September 7, 1774, 9 o’clock a.m.

When New York University established the nationally acclaimed Hall of Fame for Great Americans in 1901, Jonathan Edwards was honored as one of its first inductees and was enshrined alongside George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. Jonathan Edwards was included for the very reason of recognizing the critical role faith played in the early days of American history.

Jamestown

“On April 26, 1607, three ships carrying 104 colonists arrived at Cape Henry near modern day Virginia Beach,” parishioner Jeanne Tubman said. “We will gather around our wooden cross to pray the original prayer of the settlers.”

Pastor Robert Hunt led colonists in the following prayer 415 years ago: “We do here dedicate this colony to the glory of God, and to the advancement of the Christian faith. And by the grace of God, we will do our best to establish a new world in His name. Let His mercy and blessings be upon us as we undertake this great work. May He guide us in all our ways, and may our labor here bring forth fruit for His glory. Amen.” recorded by John Smith

This showed the settlers’ resolve and acknowledgment of their dependence on God for their well-being and success, reflecting a deeply rooted faith that guided their actions and decisions. In the face of numerous challenges, such as harsh weather conditions, scarce resources, and uncertainties of survival in a new land, their unwavering belief served as both a source of strength and a communal bond. This was a common theme among all the early settlers, who often gathered for prayer and reflection, reaffirming their commitment to each other and their mission. Their reliance on divine providence not only shaped their individual lives but also fostered a resilient community spirit that cultivated hope and perseverance amidst adversity.

A significant impact that Jamestown had was the replacing of the common store system with a compulsory work program. This shift, grounded in the biblical principles found in the New Testament where it states, “if any would not work, neither should he eat,” established a more disciplined and productive approach to labor. The implementation of this work program not only encouraged personal responsibility among settlers but also fostered a stronger sense of community, as individuals came together to contribute to the collective good. As a result, this system led to an increase in agricultural yields, thereby enhancing food production and availability. Balancing the workload among the settlers minimized idleness and promoted a spirit of cooperation, which in turn was vital for the colony’s survival and growth. Ultimately, this transition from reliance on a communal storehouse to an incentive-based labor system played a pivotal role in ensuring the sustainability of Jamestown, allowing it to thrive in a challenging environment.

Both Sir Thomas Gates and Sir Thomas Dale served as governors of the Virginia Colony. Both also came from a background of military service and from the faith of the Church of England.

Sir Thomas Gates and Sir Thomas Dale, both prominent figures in the early colonial era, firmly believed that Biblical principles were the cure for the rampant frontier savagery that often plagued their settlements. They advocated for the idea that Christianity was not only a moral compass for individuals but also the Proper Foundation for an orderly society where justice, compassion, and community could flourish. Their convictions led them to promote educational initiatives rooted in religious teachings, emphasizing the importance of instilling Biblical principles in the hearts and minds of the settlers. By fostering a culture built on faith and ethical standards, they envisioned a thriving society where the chaotic influences of the wilderness would be tamed by adherence to divine guidance, ultimately paving the way for a more harmonious coexistence among the colonists.

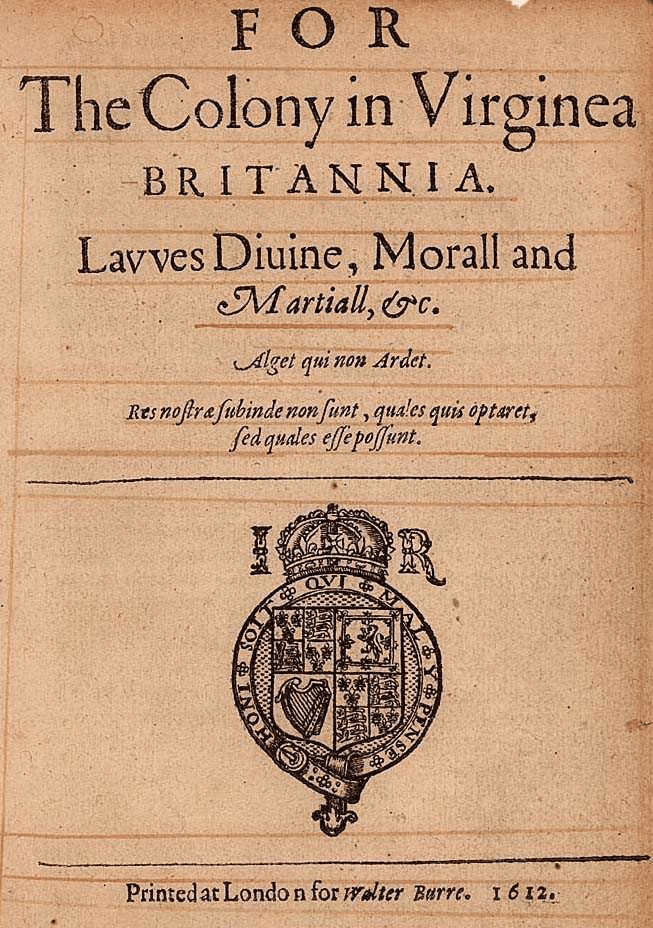

“Articles, Laws, and Orders, Divine, Politic and Martial for the Colony of Virginia,” (1612)

The laws implemented by Gates and Dale, particularly the “Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall, &c.” (often referred to as “Dale’s Laws”), were very strict regarding religious observance. These laws mandated attendance at divine service twice a day on weekdays and twice on Sundays, with severe penalties for non-compliance, including whipping and condemnation to the galleys. They also included harsh punishments for blasphemy, speaking against the Trinity, or showing disrespect to God’s word or ministers.

Sir Edwin Sandys is most notably known for his role in promoting land ownership for colonists in the Virginia Colony, particularly through his implementation of the “Headright System” which granted settlers a certain amount of land upon arrival, incentivizing migration to the New World; he served as the Treasurer of the Virginia Company and played a key role in shaping the colony’s land distribution policies. Sandys was one of the founders of the Virginia Company and joined its council in 1607. He likely helped draft the company’s second charter in 1609, which transferred control of the colony from the king to a company-appointed governor. He also helped draw up the “Great Charter” of 1618, which established the first representative assembly in North America in Virginia in 1619. This bicameral body allowed elected representatives to enact laws for the colony.

Reverend Buck opened the first session of the Virginia General Assembly, which convened in the church at Jamestown on July 30, 1619. He prayed “that it would please God to guide and sanctifie all our proceedings to his owne glory and the good of this Plantation.”

Plymouth Colony

IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience.” Anno Domini 1620 – Mayflower compact

The main purpose of the Plymouth Colony and its government, the compact stated, was to promote “the glory of God, and the advancement of the Christian faith.” This extraordinary cornerstone precedent of American law and government – the first American constitution – was thus founded not on the whims of man, but on the High Law of the Bible.

The signers of the Mayflower Compact recognized their duty to establish a community that was not only for their own welfare but also aligned with their religious convictions. This commitment added a profound layer of moral authority to their governance, distinguishing it from mere political expedience. They understood that their actions would pave the way for future generations, and so they endeavored to create a framework that would ensure justice and equality.

In the early days of the colony, the challenges were immense—harsh winters, food shortages, and the need to establish relations with the indigenous peoples. Yet, grounded in their shared beliefs and the covenant they had created, they navigated these trials with a spirit of cooperation and mutual support. The Mayflower Compact was more than just a legal document; it was a declaration of their collective identity and purpose, underscoring the importance of unity in the face of adversity.

As America evolved, the principles embodied in the Mayflower Compact would resonate throughout history, influencing the formation of future governments and constitutional documents. Its legacy lives on as a testament to the ideals of self-governance, the rule of law, and the notion of a community working together for the common good, guided by a higher moral standard. This profound connection between faith and governance remains a significant part of the American identity, reminding us of the foundational principles upon which the nation was built.

It was William Braford who cited that all credit of the Pilgrims success came from the Lord, “it was the Lord which upheld them”.

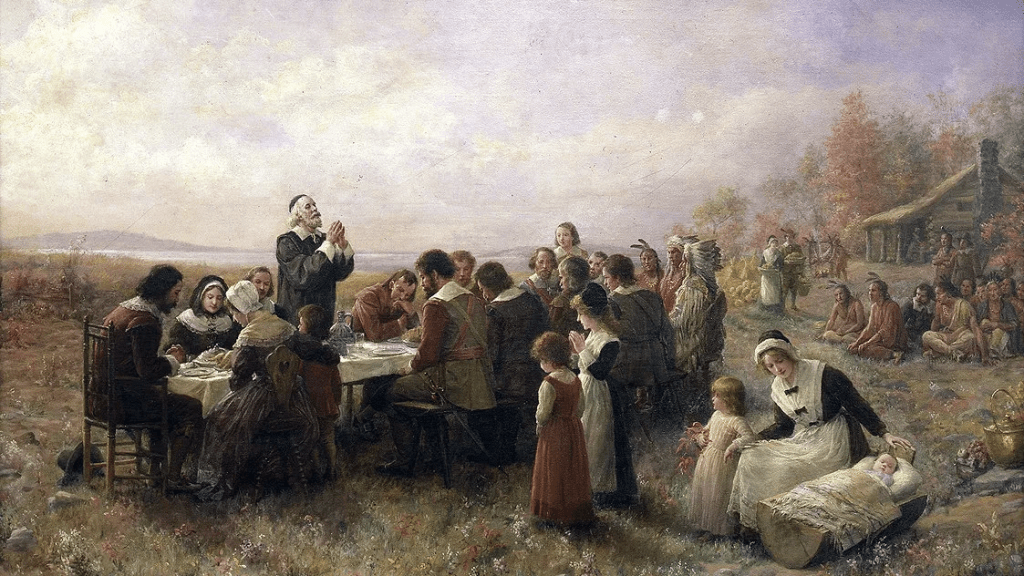

The first celebration of the American holiday Thanksgiving came from the Pilgrims’ harvest of crops, which they proceeded to give praise and thanks to God for such bounty. This momentous occasion marked not only a feast but also a profound expression of gratitude for the resources and support that sustained them in their new world. The Pilgrims, guided by their faith, believed it was their duty to acknowledge these blessings, a principle deeply rooted in their obedience to the scriptures, such as Psalm 107, which emphasizes the importance of thanking the Lord for His goodness and mercy. Through these acts of thanksgiving and praise, they set a tradition that would resonate through generations, blending faith, community, and gratitude into the fabric of American culture.

“Our Corne did proue well, & God be praysed, we had a good increase of Indian Corne, and our Barly indifferent good, but our Pease not worth the gathering, for we feared they were too late sowne………. And although it be not alwayes so plentifull, as it was at this time with , yet by the goodneses of God, we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.” E.W. (Edward Winslow) Plymouth, in New England, this 11th of December, 1621.

“Thus out of small beginnings greater things have been produced by His hand that made all things of nothing, and gives being to all things that are; and, as one small candle may light a thousand, so the light here kindled hath shone unto many…let the glorious name of Jehovah have all the praise!”

― William Bradford, Bradford: Of Plymouth Plantation

Out of the Church of England came the Virginia Colony, a significant establishment that marked the beginning of English colonial ambitions in the New World. Following this, the Separatists, seeking religious freedom and autonomy from the Church, founded Plymouth Colony, which became a refuge for those yearning for a new life based on their beliefs. As the desire for a more puritanical approach to Christian worship grew, the Puritans soon arrived, leading to the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, where they aimed to create a “city upon a hill” that would serve as a model of religious and social purity, thus significantly shaping the early landscape of America.

Puritans

The term “Puritan” was initially used mockingly for Christians wanting to cleanse the Church of England of practices they deemed unbiblical, tied to the Protestant Reformation. In 1517, Martin Luther, a Catholic priest in Germany, began this Reformation by calling for a return to essential biblical teachings. He and other Reformers emphasized salvation through God’s grace and faith in Jesus Christ alone. They taught that all Christians should be able to read the Bible independently, prioritized the Bible over Church traditions, and criticized the Church for “selling indulgences” to reduce punishment for sins. Rome rejected Luther’s calls for reform and excommunicated him, but the Reformation spread across Europe, inspiring spiritual revival and political change. It fostered the belief that everyone, including royalty, was subject to God’s Higher Law as revealed in the Bible, a concept that alarmed many European monarchs including the Kings of England.

If Martin Luther was like Apostle Peter for the Reformation, bringing the Gospel back to life, then John Calvin was like Apostle Paul, sharing the core biblical teachings that shaped the Reformation faith. The exiled English Reformers in Switzerland embraced Calvin’s ideas, not because they were new, but because they believed Calvin’s systematic theology aligned with Scripture, which they valued above all. They identified as “Calvinists” due to this belief in biblical truth, which led to many Puritans adopting the Reformed theology doctrines. In England, no group of believers was more committed to living according

to the biblical worldview than the Puritans.

The English people’s spiritual revival led them to evaluate everything, including governance, through the lens of the Bible. Many believed Christians had a duty to obey authorities unless it contradicted God’s Higher Law. In such cases, resistance was not only permissible but necessary. John Calvin emphasized that obedience to rulers should not divert one from God’s will, which should govern all authority. These Reformation principles, including the belief in Higher Law, were widely accepted by Christians in England and Colonial America.

Because of the view that the Puritans held, which was so controversial, it led to many disagreements with the English monarchs at the time. This eventually led to the Puritans leaving England due to fear of death by the ruling government. It was King James I’s desire that he wanted the Puritans to revert back to the Church of England, which would lead them to complete submission to the King rather than their Biblical views of God and His High Law. Weary of Puritan refusal to conform to the national church, the king at one point vowed: “I will make them conform themselves, or I will harry them out of the land, or else do worse.”

Over time, civil wars erupted in England, and after years of fighting, the Parliamentary forces led by Oliver Cromwell emerged victorious. However, soon after, the desire for stability and monarchy returned, resulting in the restoration of King Charles II. Many English Puritans, seeking religious freedom, chose to flee to America, unable to witness these important events. As King Charles grew more hostile toward the Puritans, creating an atmosphere of fear and persecution, Puritan leaders looked towards the New World, hoping for divine guidance. They knew about the Pilgrims’ efforts in New England and the challenges and opportunities there. Some believed it was their mission to establish a Puritan colony in America, aiming to create a society based on their beliefs. The king, viewing Puritans as a problem, was willing to help them leave England. In March 1629, he granted a charter to a Puritan group for a large area of land in New England, near the Pilgrims’ Plymouth settlement. This area would become known as the Massachusetts Bay Colony, a symbol of hope for Puritans looking to start anew.

“They desired, in fact, only the best,” wrote a knowledgeable observer, “men driven forth from their fatherland not by earthly want, or the greed of gold, or by the lust of adventure, but by the fear of God, and the zeal for a Godly worship.” So many Puritan ships departed the English ports in the 1630s that England appeared to be emptying itself. “God hath sifted a nation,” a Puritan preacher proclaimed, “that he might send choice grain into the wilderness.”

Massachusetts Bay Colony

Never had England seen such a large departure of its people. Unlike the Pilgrims on the Mayflower, they traveled in fleets—seventeen ships carried over a thousand people at one time. From 1630 to 1640, more than twenty thousand English Puritans moved to Massachusetts Bay Colony. This huge population shift was called “the Great Migration,” which significantly influenced American culture.

It would be “a City upon a hill”—a beacon of faith shining for the world to see. That was the vision described by John Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, who shared it with the Puritan passengers of the ship Arbella in March 1630. This was in reference to the Sermon on the Mount the words of Christ given in Matt 5.

“You are the light of the world. A city set on a hill cannot be hidden. -In the same way, let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven.” Matt 5:14,16

It was very clear that the Puritans had always intended this new found Colony which would later become a nation to be a beacon of light used to glorify God. Faith was at the very center of all that they did.

Within a few years of landing in June 1630, they started to set up shop and create towns, forging a new life in an unfamiliar land. Such as Charlestown, Watertown, Roxbury, Medford, and Dorchester, each community began to take shape with the hard work and dedication of its settlers. On a bayside site fed by a strong freshwater spring, they built a settlement named Boston, which would become a focal point of commerce and culture in the region, rapidly evolving from village to town to city within just a generation. In a single decade, they established more than fifty towns in the colony, each contributing to the growing network of communities that would eventually support their thriving population. Their zeal was greatly encouraged by their self-image: they viewed themselves much like the Hebrews of the Old Testament entering the Promised Land, proud of the divine mission they believed they had been chosen for. “We shall find,” Winthrop had predicted, “that the God of Israel is among us,” instilling a sense of purpose that drove the settlers to lay down roots and cultivate their new society with hope and determination for the future.

The Puritans believed that God instilled a heart for work in man, viewing honest labor as a means to honor the Lord. They took the biblical admonition to do everything for God’s glory seriously (1 Cor 10:31), emphasizing that believers should strive for excellence in every honorable task. Puritan preacher Cotton Mather noted, “It is the singular favor of God unto a man that he can attend to his occupation with contentment and satisfaction.” This strong commitment to the biblical work ethic became known as the “Puritan work ethic” for generations.

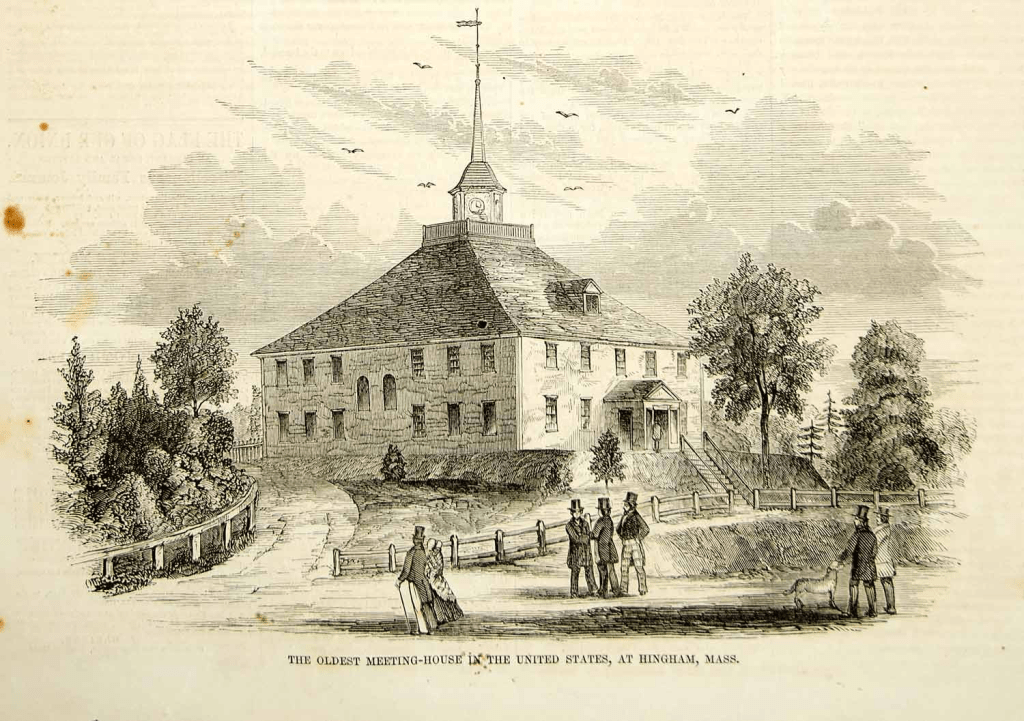

Quickly, they built their Congregational meetinghouses—raising almost forty churches in the colony’s first decade, which served not only as places of worship but also as vital community centers that fostered a strong sense of belonging among the settlers. Meanwhile, confident they were doing God’s work, they established the free enterprise system with remarkable efficiency, driven by a collective spirit that valued hard work and perseverance. They raised and sold crops and cattle, developing a flourishing fur trade that became a significant source of revenue and established connections with Native American tribes. Constructing a major shipbuilding trade enabled them to enhance their fishing industry, further securing their economic foundation. They opened trade with English colonies in the Caribbean, forging relationships that would benefit both sides, and exported tons of tobacco to England, which was highly sought after and became a staple of their export market. Absorbing nearby Plymouth Colony, they expanded their towns, built up their ports with state-of-the-art facilities at the time, and grew their markets through innovative practices and strategic partnerships. In short order, the Puritans established a tradition of successful commerce that would eventually become a hallmark of the American people, setting the stage for the dynamic economy that would follow. The Puritans’ faith-based zeal for work would inspire the American free enterprise system—which would one day become the envy of the world, showcasing the potency of merging spiritual conviction with industriousness in a new land filled with promise and opportunities.

“In the popular mind,” Clarence Ver Steeg would note, “the Puritans [were once viewed as] the purest of men, the embodiment of all that was best in humankind…[renowned for] hard work, good judgment, faith, uprightness, unimpeachable motives, and the seat of representative government.”

They held to the view that life should not be divided into religious and secular parts; everything should revolve around the Bible and God— including worship, family, work, play, education, arts, law, and government. All actions should honor God, especially within family life. They believed God made the family before the church, seeing it as a blessing, the foundation of society, and a place to train young followers of Christ. The family flourished in Puritan New England, and the historic values that would define the American family for centuries were in large part the legacy of the Puritans’ biblical faith. “The sense of spiritual fellowship gave a new tenderness and refinement to common family affections,” according to English scholar John Richard Green. “Home, as we conceive it now, was the creation of the Puritan.”

Because the family was so crucial for the Puritans success so was education. They had first hand account of abuse of others because of illiteracy, therefore they sought to prevent it among the colonies. One way they went about this was by establishing “The Old Deluder Satan Law” —so named because the

Puritans believed Satan used illiteracy as a weapon against biblical truth.

For the same reasons—to know God’s Word and to understand His creation—the Puritans established colleges in America, believing that education was essential for spiritual growth and societal improvement. The first of these institutions was Harvard University, founded in 1636, which was set up as a bastion of faith-based learning amidst a burgeoning new world. “Let every Student be plainly instructed and earnestly pressed to consider well,” read the Harvard admissions requirements, “the main end of his life and studies is to know God and Jesus Christ which is eternal life (John.17:3) and…the only foundation of all sound knowledge and learning.” This commitment to a curriculum that intertwined piety and intellect was a hallmark of the time, ensuring that every scholar understood their relationship with the divine while pursuing the truth about the world around them, thereby fostering an environment where both faith and reason could flourish together.

The Puritans also produced the first book published in America, the Bay Psalm Book of 1640, and the first textbook—the New England Primer. Written by an unknown Puritan in about 1690, the New England Primer used stories and passages from the Bible to teach reading skills and character training. More than three million copies would be put in the hands of schoolchildren over the course of a century, and its lessons would be recited by generations of Americans. Because of this many of America’s founding fathers would learn the concept of Higher Law by studying the Westminster Catechism in the New

England Primer.

Great Providence

Roger Williams established a new colony. He called it Providence—so named because of “God’s merciful providence to me in my distress,” he said. “I designed it might be for a shelter for persons distressed for conscience,” he would later write.

It grew into the Colony of Rhode Island—the first colony in America to grant full religious liberty. There, in the wilderness of Rhode Island, Williams moved from Congregationalist to Baptist. At his request, a layman baptized him by immersion. Then he baptized the layman—and set about baptizing others. His new congregation laid claim to being the first organized Baptist church in America.

Now, know ye, that we, being willing to encourage the hopeful undertaking of our said loyal and loving subjects, and to secure them in the free exercise and enjoyment of all their civil and religious rights, appertaining to them, as our loving subjects…and because some of the people and inhabitants of the same colony cannot in their private opinions, conform to the public exercise of religion, according to the liturgy, forms and ceremonies of the Church of England…our royal will and pleasure is, that no person within the said Colony, at any time hereafter, shall be any wise molested, punished, disquieted, or called in question, for any differences in opinion in matters of religion.… – Roger Williams

To Williams, freedom of religion and the separation of church and state did not mean abandoning the biblical foundation of English law or suppressing every vestige of Bible-based morality in government; instead, it meant that there should be no government-sponsored denomination, such as the Church of England, and that everyone should be allowed to believe and worship according to his or her conscience. He did not originally intend to become a champion of religious liberty; he mainly wanted to purge Puritanism of its connection to the Church of England.

It is important to note that the religious freedom that Roger Williams and many others sought was not the freedom of other religions such as Hinduism, Islam, or Buddhism, but that which was within Christianity. This would be the freedom to belong to any Biblical-believing Protestant denomination, not the freedom to be anything other than Christian. The emphasis was on creating a society where diverse interpretations of Christian doctrine could flourish, allowing individuals to explore their faith in a personal and authentic manner. This pursuit was deeply rooted in the belief that personal conscience should guide an individual’s relationship with God, promoting a sense of community among those who shared similar beliefs while still navigating the complexities of differing Christian practices. Ultimately, the quest for religious freedom during this time was a reflection of a broader yearning for spiritual authenticity and the right to practice one’s faith without coercion or interference from external authorities.

His death occurred only six years before English Parliament passed the 1689 Act of Toleration, which granted freedom of worship to Protestant nonconformists. The Toleration Act did not apply to Quakers, Catholics, or Jews, who still faced restrictions, but it allowed dissidents such as the Puritans, Presbyterians, Dutch Reformed, and Baptists freedom to preach, teach, and worship outside the Anglican Church. Due to the Reverend Williams, such freedom already existed in large measure within the Colony of Rhode Island.

William Penn and Pennsylvania

William Penn found himself in a unique situation: The king of England owed him a lot of money. The debt had originally belonged to Penn’s father, an admiral in the English navy, whose family connections with a mercantile empire had allowed him to amass a fortune. At the time, the future king— Charles II—was the duke of York, and Admiral Penn had loaned him a large sum at a critical time. Upon the admiral’s death, ownership of the loan passed to his son. In 1681, two years before aging Roger Williams died in Rhode Island, William Penn decided to collect the debt he had inherited. Instead of money, Penn explained to the king, he wanted land in America— and the king granted his request.

William Penn was a Quaker, and his heart’s desire was for a Quaker colony in this new granted land of Pennsylvania

“Remonstrance against the Law against Quakers.” It argued that Christians had a biblical obligation to assist those in need, regardless of their beliefs, based on Christ’s command that “whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.”

Master, we are bound by the Law to do good to all men, especially to those of the Household of faith…so love, peace and liberty extending to all in Christ Jesus condemns hatred, war and bondage. [Our] desire is not to offend one of his little ones in whatsoever form, name or title he appears in, whether Presbyterian, Independent, Baptist or Quaker…desiring to do unto all men as we desire all men should do unto us…for our Savior saith this is the Law and the Prophets.

The Colony of Pennsylvania would be, in Penn’s words, a “Holy Experiment”—a faith-based colony that offered expanded religious liberty to everyone. To William Penn, it was all done in the name of Christ. “True godliness does not turn men out of the world,” he wrote, “but enables them to live better in it; and excites their endeavors to mend it; not to hide their candle under a bushel, but to set it upon a table in a candlestick. … Christians should keep the helm, and guide the vessel to port; not…leave those that are in it without a pilot.”

Unlike the Puritans, who believed that laws and law enforcement were necessary to restrain humanity’s sinful nature, Quakers considered mankind to be essentially good, so Penn and others launched the Colony of Pennsylvania with scant laws. A crime wave of sorts soon made them reconsider the need for law and order. To deal with the sins that beset the colony’s growing population, Quaker authorities implemented an expanded criminal code that resembled Puritan laws in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Pennsylvania’s Quaker population was eventually outnumbered by non-Quakers, which resulted in a shift in political leadership as well. Pennsylvania would long be considered the “Quaker Colony,” but Quakers became the religious minority. Even so, the Quakers’ “Holy Experiment” in Pennsylvania reinforced Colonial America’s Christian values and became a model for religious liberty. William Penn, the Puritan-turned Quaker whose biblical faith inspired the founding of three colonies, lived until age seventy-five. In his final years, he proposed another grand concept for America. England’s leaders ignored it, but it too proved to be visionary. His proposal? A union of all the American colonies, governed by a colonial congress.

Conclusion

Was America intended to be a Christian nation? Yes. Was America ever a Christian nation? Yes! Is America currently a Christian nation? No.

But as you can see throughout all these small examples, the Christian faith was their leading backbone and motivation, deeply influencing their decisions and actions. The intention of the early colonies was to settle a nation where freedom and faith could be exercised by all Christians alike, fostering an environment of spiritual growth and collaboration among diverse groups. This quest for religious liberty not only shaped their communities but also laid the groundwork for future generations to embrace the same beliefs. All the founding fathers would have been raised in such a Christian-based culture that would have played a heavy influence on their beliefs, instilling in them the values of morality, integrity, and the importance of serving a higher purpose. These principles guided their establishment of a nation that would prioritize individual rights and the pursuit of happiness as fundamental tenets of one nation under one God.

Through a diversity of Bible-based beliefs, Colonial America firmly founded its culture, laws, and government on a Christian worldview. That common faith was clearly expressed in the founding documents of all thirteen American colonies:

The Massachusetts Bay Colony’s charter recorded an intent to spread

the “knowledge and obedience of the only true God and Savior of

mankind, and the Christian faith,” much as the Mayflower Compact

cited a commitment to “the Glory of God, and Advancement of the

Christian faith.”

Connecticut’s Fundamental Orders officially called for “an orderly and

decent Government established according to God” that would

“maintain and preserve the liberty and purity of the Gospel of our

Lord Jesus.”

In New Hampshire, the Agreement of the Settlers at Exeter vowed to

establish a government “in the name of Christ” that “shall be to our

best discerning agreeable to the Will of God.”

Rhode Island’s colonial charter invoked the “blessing of God” for “a

sure foundation of happiness to all America.”

The Articles of Confederation of the United Colonies of New England

stated, “Whereas we all came into these parts of America with one

and the same end and aim, namely, to advance the Kingdom of our

Lord Jesus Christ and to enjoy the liberties of the Gospel …”

New York’s Duke’s Laws prohibited denial of “the true God and his

Attributes.”

New Jersey’s founding charter vowed, “Forasmuch as it has pleased

God, to bring us into this Province…we may be a people to the praise

and honor of his name.”

Delaware’s original charter officially acknowledged “One almighty

God, the Creator, Upholder and Ruler of the World.”

Pennsylvania’s charter officially cited a “Love of Civil Society and

Christian Religion” as motivation for the colony’s founding.

Maryland’s charter declared an official goal of “extending the

Christian Religion.”

Virginia’s first charter commissioned colonization as “so noble a work,

which may, by the Providence of Almighty God, hereafter tend to

the…propagating of Christian Religion.”

The charter for the Colony of Carolina proclaimed “a laudable and

pious zeal for the propagation of the Christian faith.”

Georgia’s charter officially cited a commitment to the “propagating of

Christian religion.”

Colonial America was constructed, one colony at a time, on two pillars

—faith and freedom.

Day of solemn fasting and prayer March 20 1797 – Samuel Adams “As the safety and prosperity of nations ultimately and essentially depend on the protection and the blessing of Almighty God, and the national acknowledgment of this truth is not only an indispensable duty which the people owe to Him, but a duty whose natural influence is favorable to the promotion of that morality and piety without which social happiness can not exist nor the blessings of a free government be enjoyed…….. offer their devout addresses to the Father of Mercies agreeably to those forms or methods which they have severally adopted as the most suitable and becoming; that all religious congregations do, with the deepest humility, acknowledge before God the manifold sins and transgressions with which we are justly chargeable as individuals and as a nation, beseeching Him at the same time, of His infinite grace, through the Redeemer of the World, freely to remit all our offenses, and to incline us by His Holy Spirit to that sincere repentance and reformation which may afford us reason to hope for his inestimable favor and heavenly benediction”

*This Article was influenced by the book “Forged In Faith” by Rod Gragg and multiple others studies.

Leave a comment