“Christianity, if false, is of no importance, and if true, of infinite importance. The only thing it cannot be is moderately important.” – C. S. Lewis

This is probably no shocker to most, but my expertise isn’t in Bible apologetics. However, I place my full trust in that it is the complete word of God for many reasons related to Faith and historical evidence. It is the inerrant infallible inspired word of God though and though. It is one of the main foundations of the Christian belief, without it there would be no true knowledge of Christ, The Law, and Eternal life. If we lower our view on it any small degree, then we cannot fully rely on it and or trust that it is different than any other book in history. Apart from it we would be lost and left to our confusion in a wicked broken world. Below will be a video and material from Wesley Huff, who is a incredibly gifted apologetics teacher regarding the trustworthiness of the Bible. He goes into great details with abundance of evidence that supports the claim that our Bibles today are the most accurate true message of the first hand writing of those of Christ and his followers. He explains why we can place our full trust and faith in it.

The History Of The Bible

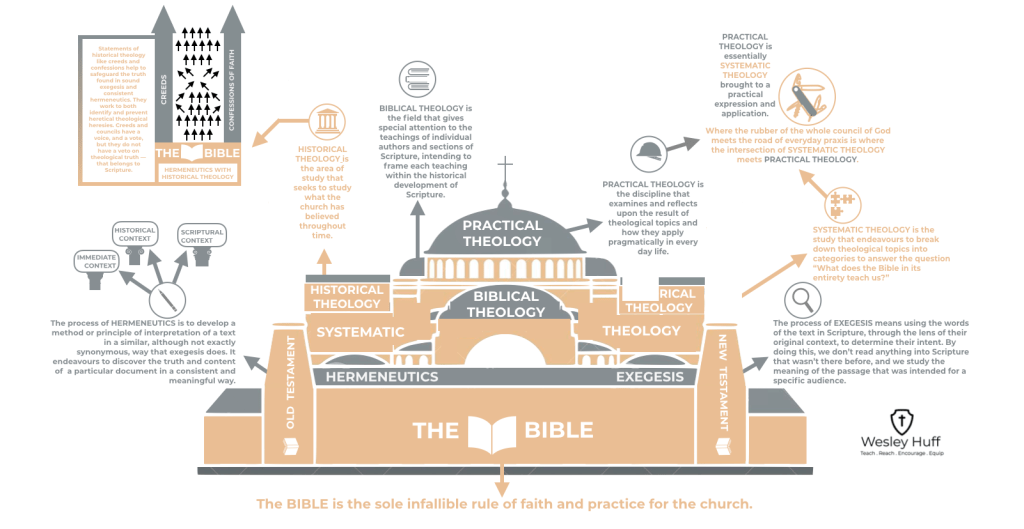

Canon – derived from the ancient Greek word kanōn (κανών) and the Semitic kánna (קָנֶה), was a word that originally referred to a reed stick. These sticks were used as measuring rods, and eventually the word became synonymous with the idea of a “standard” by which something was measured. Within early Christianity the idea of a “standard” by which someone discerned the proper books considered scripture was talked about under the category of what was or wasn’t “canonical.” The final canonical list that we use today finds its shape and order from Athanasius’ Festal Letter (367 AD). Athanasius’ writing however, wasn’t a pronouncement of the canon, but merely a list of the books that had already been established and recognized as scripture for the centuries leading up to it.

Apocryphal – originating from the Greek word apocryphos (ἀπόκρυφος) meaning “strange,” “hidden,” or “secret.” The term became synonymous with non-canonical writings. It became customary within early Christianity to use the description of “apocryphal” for books that were being touted or considered scripture but did not have authentic connections for the criteria of canonicity.

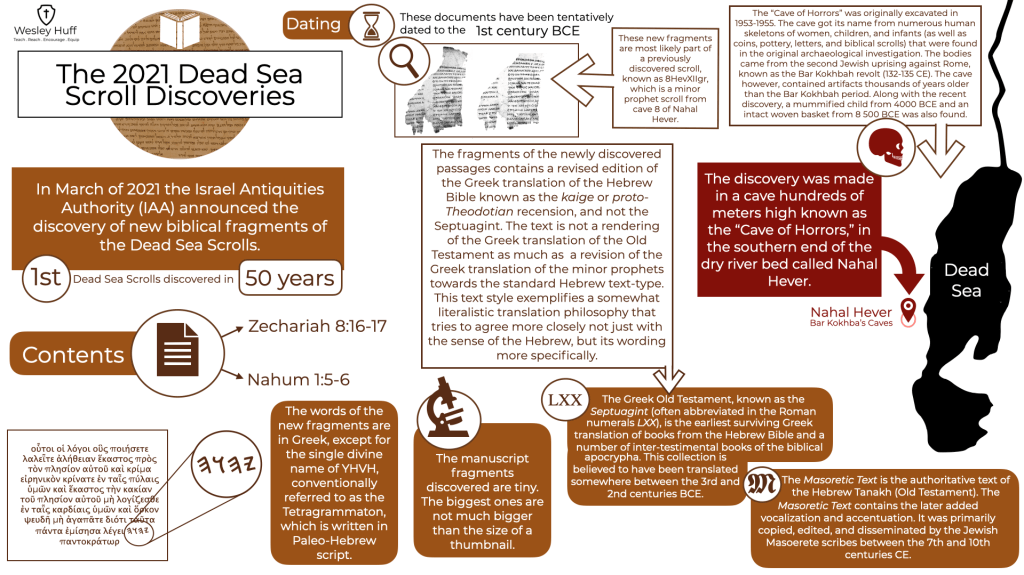

Dead Sea Scrolls – a collection of 970 scrolls, dating between the third century BC and the first century AD, discovered in caves spread down the coast of the Dead Sea that exist in various stages of completeness. Although we are not entirely sure who wrote, copied, and stored all of the Dead Sea Scrolls, most of them are the product of the Jewish sect known as the Essenes. This collection includes all the books of the Old Testament (excluding Esther), as well as a number of Jewish books of theology and history. The preservation of these documents ranges from entire scrolls (like the Great Isaiah Scroll) to mere scraps of papyrus and parchment only millimeters in size.

The Differences In Translations

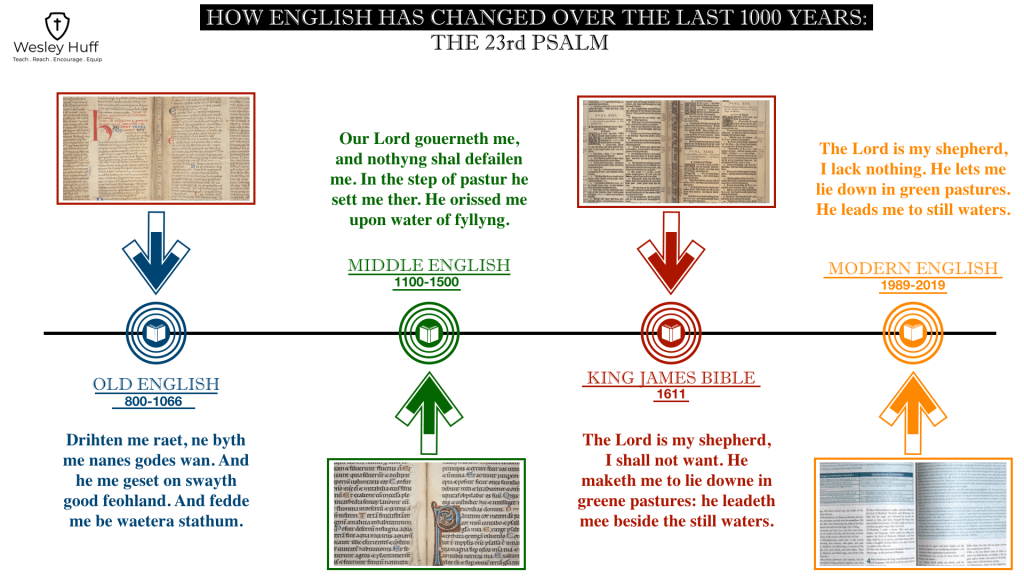

Bible – stemming from the Koinē Greek word biblia (βιβλία), meaning “books,” this is the term that became associated specifically with “the books” of Christian scripture. The term in an ancient context would have meant “scroll” and is used several times within Scripture. For example, in Revelation 5:2, an angel asks the question “Who is worthy to break the seal and open the scroll (to biblion – τὸ βιβλίον).” In our modern Protestant context, the Bible would refer explicitly to the 66 books of the Old and New Testaments.

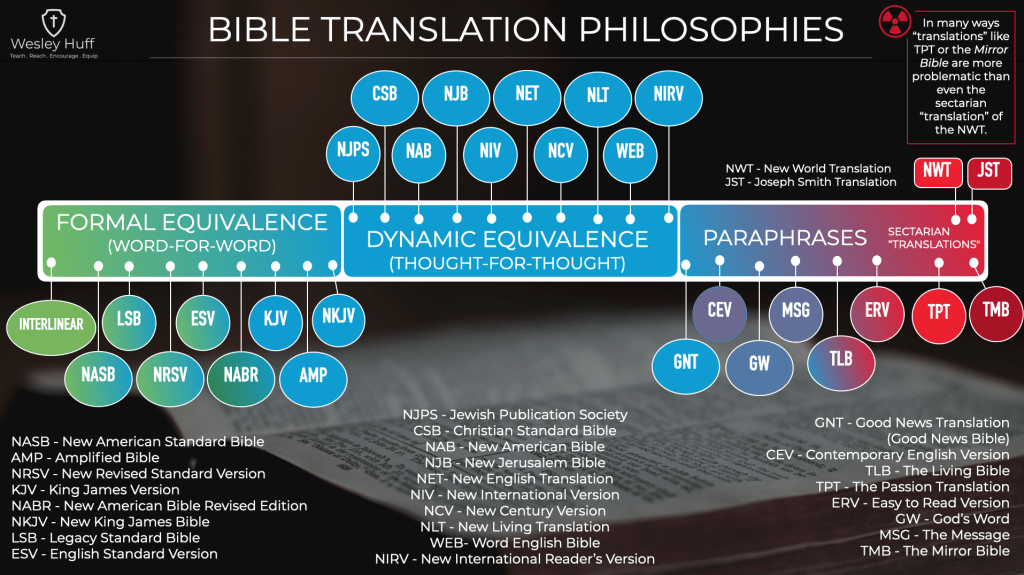

Septuagint – a modern term that refers to a stream of ancient translations into Greek of the Hebrew Bible and several other Jewish texts (also known by the abbreviation LXX). The translation project of the documents we now call the Septuagint took place between the third and first centuries BC. Many of the Greek quotations of the Old Testament found within the New Testament are quotations from the Septuagint.

Practical Side Of This Conclusion

*all this information above can be found on His site https://www.wesleyhuff.com/infographics

Hopefully, this has helped bring you more resolve around the topic of the Bible’s authenticity and the many ways it has stood the test of time, demonstrating its reliability through historical corroborations and archaeological discoveries. It is essential to recognize that the Bible is not just a book but a profound source that can be truly trusted for the Gospel message of Christ. By diving deeper into its teachings and the context in which it was written, one can better appreciate its depth and the unwavering truth and joy it offers to believers.

For more information and trusted sources, Please check out https://www.wesleyhuff.com/can-i-trust-the-bible

Leave a comment