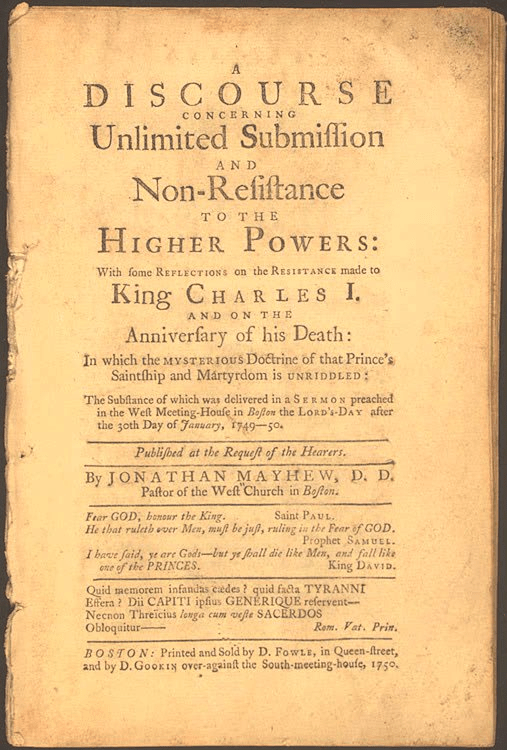

Rev. Jonathan Mayhew (1720–1766) was a minister in Boston known for his bold sermons and strong belief in both religious freedom and political liberty. Educated at Harvard College, he became pastor of Boston’s West Church in 1747, where he served for nearly two decades. Mayhew often challenged traditional religious views, emphasizing reason, personal conscience, and moral responsibility in matters of faith. He believed that religion should not rely on strict authority or fear, but instead be guided by thoughtful understanding and a commitment to justice. He came from a long line of Puritan ministers and was educated in Puritan-influenced New England, but he challenged the traditional beliefs of Puritanism, especially its emphasis on religious authority, intolerance, and rigid doctrine. Instead, Mayhew promoted rational Christianity, religious tolerance, and individual conscience—ideas that aligned more with the Enlightenment than with classic Puritan theology. His progressive ideas drew both support and criticism, helping to shape a more open and independent spirit in colonial America.

It is hoped that but few will think the subject of it an improper one to be discoursed on in the pulpit, under a notion that this is preaching politics instead of CHRIST. However, to remove all prejudices of this sort, I beg it may be remembered that “all scripture ⎯ is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for CORRECTION, for instruction in righteousness.” Why, then, should not those parts of scripture which relate to civil government be examined and explained from the desk as well as others? Obedience to the civil magistrate is a Christian duty: and if so, why should not the nature, grounds and extent of it be considered in a Christian assembly? . . .

ROM. XIII. 1:⎯⎯7.

“1Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers For there is no power but of God: the powers that be, are ordained of God. 2Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God: and they that resist, shall receive to themselves damnation. 3For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? do that which is good, and thou shalt have praise of the same: 4For he is the minister of God to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil, be afraid; for he beareth not the sword in vain: for he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doth evil. 5Wherefore ye must needs to be subject, not only for wrath, but also for conscience sake. 6For, for this cause pay you tribute also: for they are God’s ministers, attending continually upon this very thing. 7Render therefore to all their dues: tribute to whom tribute is due; custom, to whom custom; fear, to whom fear; honour, to whom honour.”

The apostle’s doctrine, in the passage thus explained, concerning the office of civil rulers and the duty of

subjects [the people] may be summed up in the following observations;

THAT the end of magistracy is the good of civil society, as such:

THAT civil rulers, as such, are the ordinance and ministers of God; it being by his permission and

providence that any bear rule; and agreeable to his will, that there should be some persons vested with

authority in society, for the well-being of it:

THAT which is here said concerning civil rulers, extends to all of them in common: it relates

indifferently to monarchical, republican and aristocratical government; and to all other forms which truly

answer the sole end of government, the happiness of society; and to all the different degrees of authority

in any particular slate; to inferior officers no less than to the supreme:

THAT disobedience to civil rulers in the due exercise of their authority, is not merely a political sin,

but an heinous offence against God and religion:

THAT the true ground and reason of our obligation to be subject to the higher powers, is the

usefulness of magistracy (when properly exercised) to human society, and its subserviency to the general

welfare:

THAT obedience to civil rulers is here equally required under all forms of government, which

answer the sole end of all government, the good of society; and to every degree of authority in any state,

whether supreme or subordinate:

(From whence it follows, THAT if unlimited obedience and non-resistance be here required as a duty under any one form of government, it is also required as a duty under all other forms; and as a duty to subordinate rulers as well as to the supreme.)

AND lastly, that those civil rulers to whom the apostle enjoins subjection, are the persons in

possession; the powers that be; those who are actually vested with authority.

THERE is one very important and interesting point which remains to be inquired into; namely, the

extent of that subjection to the higher powers, which is here enjoined as a duty upon all christians. Some

have thought it warrantable and glorious to disobey the civil powers in certain circumstances; and, in

cases of very great and general oppression, when humble remonstrances fail of having any effect; and

when the publick welfare cannot be otherwise provided for and secured, to rise unanimously even against

the sovereign himself in order to redress their grievances; to vindicate their natural and legal rights: to

break the yoke of tyranny and free themselves and posterity from inglorious servitude and ruin. . . .

But in opposition to this principle, it has often been asserted that the scripture in general (and the passage under consideration in particular) makes all resistance to princes a crime in any case whatever ⎯ If they turn tyrants and become the common oppressors of those whose welfare they ought to regard with a paternal affection, we must not pretend to right ourselves unless it be by prayers and tears and humble entreaties. And if these methods fail of producing redress, we must not have recourse to any other, but all suffer ourselves to be robbed and butchered at the pleasure of the Lord’s anointed: lest we should incur the sin of rebellion and the punishment of damnation. For he has God’s authority and commission to bear him out in the worst of crimes, so far that he may not be withstood or controlled. Now whether we are obliged to yield such an absolute submission to our prince, or whether disobedience and resistance may not be justifiable in some cases, notwithstanding anything in the passage before us, is an inquiry in which we are all concerned; and this is the inquiry which is the main design of the present discourse. . . .

I now add, farther, that the apostle’s argument is so far from proving it to be the duty of people to obey and submit to such rulers as act in contradiction to the public good, and so to the design of their office, that it proves the direct contrary. For, please to observe, that if the end of all civil government be the good of society; if this be the thing this is aimed at in constituting civil rulers, and if the motive and argument for submission to government be taken from the apparent usefulness of civil authority; it follows, that when no such good end can be answered by submission, there remains no argument or motive to enforce it; if instead of this good end’s being brought about by submission, a contrary end is brought about, and the ruin and misery of society effected by it, here is a plain and positive reason against submission in all such cases, should they ever happen. . . . Suppose God requires a family of children to obey their father and not to resist him; and enforces his command with this argument; that the superintendence and care and authority of a just and kind parent will contribute to the happiness of the whole family; so that they ought to obey him for their own sakes more than for his. Suppose this parent at length runs distracted and attempts, in his mad fit, to cut all his children’s throats. Now, in this case, is not the reason before assigned, why these children should obey their parent while he continued of a sound mind, namely, their common good, a reason equally conclusive for disobeying and resisting him, since he is become delirious and attempts their ruin? It makes no alteration in the argument whether this parent, properly speaking, loses his reason; or does, while he retains his understanding, that which is as fatal in its consequences as any thing he could do, were he really deprived of it. This similitude needs no formal application. . . .

What unprejudiced man can think that God made ALL to be thus subservient to the lawless pleasure and frenzy of ONE, so that it shall always be a sin to resist him!

To conclude: Let us all learn to be free, and to be loyal. Let us not profess ourselves vassals to the lawless pleasure of any man on earth. But let us remember, at the same time, government is sacred and not to be trifled with. It is our happiness to live under the government of a PRINCE who is satisfied with ruling according to law, as every other good prince will ⎯ Let us prize our freedom, but not use our liberty for a cloak of maliciousness.

‘Woe to those who call evil good and good evil, who put darkness for light and light for darkness, who put bitter for sweet and sweet for bitter! ‘ – Isaiah 5:20

Leave a comment